Originally written March 21, 2014

Introduction

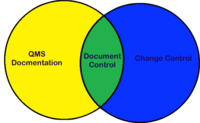

The documentation of an organization’s Quality Management System (QMS) is required by many regulatory and standards bodies, including the US FDA and ISO-9001. Properly implemented, this documentation allows for clear, traceable communication of the an organization’s quality standards, processes, and other critical information. Because processes and their related documents need to change over time, document control is used to ensure:

- Traceability of changes in documentation

- Appropriate and adequate approval of changes

- Old versions of the documentation are no longer available for use

- New versions of the documentation are readily available for use

A document management system (DMS) is any tactic used to organize and administer access to documents. It is a tool that is required to execute document control in most Quality Management Systems. Since computer-generated document has become the norm for most organizations, there has been a push to move away from traditional paper-based DMSs and towards electronic system (eDMS).

A document management system (DMS) is any tactic used to organize and administer access to documents. It is a tool that is required to execute document control in most Quality Management Systems. Since computer-generated document has become the norm for most organizations, there has been a push to move away from traditional paper-based DMSs and towards electronic system (eDMS).

Purpose

The purpose of this opinion is to explore some of the common mistakes made when implementing an electronic document management system that is to be used for document control.

Scope

The scope of this document is limited to electronic document management systems used for document control. It will not cover other content management systems or other uses for EDMSs.

Analysis

Requirements of a Document Management System

Workflow

In its simplest terms, most Document Control procedures have the same basic workflow:

- Document Change Order (DCO Request) — Initiation of change, which describes what and why a change is needed.

- Change Execution — The changes are made to the document. This is often a collaborative effort, where the changes of one or more contributors are collected and reconciled until a version is ready for approval.

- DCO Review — Acceptance of change request by manager of process principal results in the new version being released for use. Rejection of the request results in the current version persisting in production use. The decision point must be recorded.

- Historical Archiving — The previous version is stored and taken out of use once a new version is approved. Obsolete documents are also archived in a similar manner.

- Change Notification — When the controlled document describes a process, policy or procedure, staff and euqipment following the instructions need to be identified and notified that a new version is in effect and must be re-trained or re-configured.

Statuses and Access Rights

There are usually three different statuses of a document lifecylcle following the aforementioned workflow, each status has different access rights associated with it:

- Draft — open for both viewing and editing by few or many, depending on the organization.

- Released/Approved — open for viewing only for many. A system administrator or process lead may have access to edit the document for cosmetic changes. Easy and appropriate access is vital for adherence to written policies and procedures

- Archived/Obsolete — Not viewable by most. Not editable by anyone. A system administrator or process lead may have access to view.

Identification of Controlled Document

With the proliferation of type-writing and word processing, one could not only rely on recognizing the original author’s handwriting in order to identify the authentic and original controlled document. It is vitally important to be able to identify the current, released version of a controlled document from its predecessors, copies and altered iterations.

Record Keeping

The final aspect of a document management system is establishing traceability of the document identification, change requests and approval, as well as document history logs. The importance of such a log becomes apparent during troubleshooting of an issue. During a historical review, it may be critical to identify exactly which version of one or more procedures was in effect during the time of the issue.

Paper-based Systems

For the majority of the last century, the only way to document information was by writing, typing or printing on paper. Access was controlled physically by locking binders in cabinets or rooms. Change request were processed in folders or binders with a change request form as a coversheet and the proposed new version behind it. The signed copies of the DCOs were catalogued for record-keeping and a blue wet-ink signature often served as controlled copy authentication (copies made with a black & white copier would show the signature in black). Stamps were often used for documenting the status of the document, while meetings (later emails) were the only way to notify others of the change. If you wanted a copy of the controlled document, you would have to ask the “Doc Control Guy” to get it out and make you a copy or sign it out to you.

This manual and tedious process is only as effective as the staff who are asked to follow it, much to the dismay of quality managers and document control analyst. Audits and inspections often show that uncontrolled copies are in circulation because the teams did not want to be slowed down by document control or limited access to their documents. Copies of old versions of a document are often found in drawers or worse; in the hands of the technician.

Large and older companies could end up having giant rooms (even buildings) of document archives. Finding an old copy for a particular date range could take an entire day. Thankfully, computers came around, so all of these problems are automatically solved, right?

Switching to Electronic Systems

One of the first major changes in document control came as the price of electronic data storage locally-hosted file servers started to fall. Now that entire building of historical data can fit in one server room, but many of the other issues mentioned above continue.

Why?

The biggest mistake organizations make when switching to eDMSs is not changing their approach to document control. Many times, organizations simply electronify their paper-based system. Instead of a hard copy locked in a cabinet, they now have a soft copy locked on a harddrive or server. If you are still relying on one or a few people giving you access to the controlled document, you did not alleviate the issue of limited access. If anyone can take a copy of a controlled document and alter it without being able to distinguish it from it from the controlled version, you have lost control over your documents. If you print the documents, then scan them and put them into document control, you did not save any trees, plus you’ve lost the powers of searching the content of the document and the ability to change the actual controlled document for the next revision.

The second biggest mistake organizations make is not effectively implementing eDMS solutions. Companies can spend thousands of dollars on a solution that does not meet all of the criteria listed above because of some other feature that wowed them. Sure, you can make pretty fonts or collaborate with 50 people at a time, but if there is no approval workflow, you still have to use your manual method. The same can be true for companies who spend a great deal of money for licenses to a perfectly-suited solution, but don’t spend what it takes to implement the functionality that makes the software so great.

Conclusion

Like any DMS, an electronic document management system is only as effective as the document control process it supports. A document control process is only as good as the team that designs and enforces it. One should not expect to change the quality and/or ease of their organization’s document control process simply by changing the way the data is stored.

If you want a more efficient and effective process, change the process, and find tools that allow for you to implement the change. You do not have to spend a fortune to do so either. There are open-source solutions available as well as simple tools that your organization already uses that can greatly improve your system (if you know how to use them).

An organization’s documents should be valued as an asset and a liability. Learn from them. Use them. Protect them.

References

- Guidance on the Documentation Requirements of ISO 9001:2008

NO EVENT SHALL LAB INSIGHTS, LLC BE LIABLE, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, TORT, WARRANT, OR UNDER ANY STATUTE OR ON ANY OTHER BASIS FOR SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, INDIRECT, PUNITIVE, MULTIPLE OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES IN CONNECTION OR ARISING FROM LAB INSIGHTS, LLC SERVICES OR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT.